|

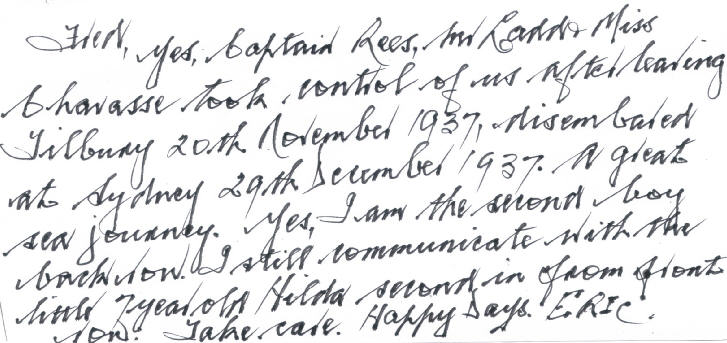

EXPLOITED: Boys are 'trained' on a UK farm around 1900, above, before being sent overseas to work; left, child migrants arrive

in Australia shortly after the Second World War

Child poverty is still an Issue today but in the past, poor children were sent away to Australia and Canada to find new lives.

YORK MEMBERY looks at this forgotten chapter of British history

REARED on a diet of adventurous stories about the Canadian wild west and life Down Under, many child migrants set sail from

Britain full of hope for the future. However, the reality that awaited them across the seas often fell far short of the dream as some of

their letters home illustrate.

"I am sick of living," wrote one girl. "The first place I was sent I had to work so hard that I was nearly laid sick with consumption.

I am so homesick."

The dispatch of thousands of Britain's impoverished youngsters to the colonies in the 19th and 20th centuries was perhaps the

greatest forced mass migration of children in history.

Now, In the moNt comprehensive look yet at the subject, a new book, New Lives For Old: The Story Of Britain's Home Children,

which draws upon previously unpublished documents in the National Archives, tells the full of this questionable chapter in British

history.

Child migration was pioneered by two Victorian women, Maria Wye and Annie Macpherson, their aim being to Hive Britain's street

children the chance of a new life in the Empire's wide open spaces at a time of appalling poverty.

In 1869, Wye launched her project with an appeal for money to take "gutter children" to the colonies. Later that year she took her

first party - of workhouse girls aged five to 11 - to Canada.

The following year Macpherson, a Scotswoman moved by the plight of the East End's poor, bought a farm in Canada for the

purposes of training deprived British boys and girls for work on the colony's farms.

CHILD migration was driven by more than an evangelical zeal to save street urchins from the workhouse. It was also fuelled by a

puritanical desire to remove them from the "temptations" of the big city where they might fall into a life of crime, as well as a

Victorian sense of thrift: resettling them in the colonies would cost just £10 per child.

But as early as 1875, a report criticised child migration, accusing the agencies involved of being little more than "schemes for

providing cheap labour" and making "100 per cent profit" on each child sent out.

It was particularly critical of Wye's home in Canada where it found evidence of cruelty, noting that one girl was kept "in solitary

confinement for 11 days upon bread and water". Moreover, "adoption" could just as easily mean servitude. "Adoption is when folks

get a girl to work without wages," said one child.

Despite the initial furore, so great was the child poverty problem that the agencies were soon sending out even more children. Other

organisations, such as the National Children's Home, also got in on the act. However the biggest player of all would be Barnardo's

which from 1882-1939 would send more than 30,000 children across the Atlantic, boys being sent to a farm school, girls being

placed as domestic servants.

Children had to be "sound and healthy in body" and if they failed a medical before leaving England they were sent home.

"They found something wrong with my sister's eye and wouldn't let her come with me," wrote one Barnardo's girl tearfully.

"I was heartbroken."

The voyage across the North Atlantic could also be a frightening experience. Children slept in bunks "in a sardine-like arrangement".

And the weather was often terrible. One adult escorting a party of children recorded: "Tues, 29th. At 4am, nearly all pitched out of

our hammocks by the rolling of the ship... severe gale blowing... at breakfast the tables were swept of dishes and food... Everyone

holding on by anything they could catch."

On reaching the New World, siblings were often sent to different homes. But the most questionable aspect of Barnardo's child

migration work was what was called "philanthropic abduction" - the taking away of children from parents who led immoral lives.

"Some children were sent to Canada to distance them, quite literally, from their families," observe the book's authors.

In all, one in 20 Barnardo's boys and one in 10 girls were sent to Canada without their parents' consent. So great were the numbers

being sent out to Canada that its initial enthusiasm for child migrants began to wane and they were increasingly treated as second

class citizens. One girl wrote that her mistress referred to her as "the girl from the Home".

Records show that some children were also whipped, beaten and sexually assaulted. Two Barnardo's boys reportedly even committed

suicide. The most famous case of abuse involved a boy called George Green who in 1895 was found dead in an upstairs room of the

farm where he was sent, emaciated and covered in welts.

HOWEVER, by then the mood in Canada had swung so vehemently against "home children" that not long afterwards one paper, the

Toronto Evening Star, fumed: "No law too strict can be framed to prevent these waifs, handicapped by heredity, from mingling with

the pure and healthy children of this country."

By the First World War, growing humanitarian concerns were also coming into play - and in the Twenties, having taken in 100,000

child migrants, Canada effectively outlawed such migration.

Still, other parts of the Empire -notably Australia - were eager to provide a home for Britain's young urban poor. And thousands were

sent out under the "farm school" scheme to train boys for outdoor work and girls for domestic service.

In 1913, the first contingent - 12 workhouse boys from the East End - arrived at the first such school near Perth, Western Australia.

The movement soon attracted royal patronage and in 1934 the Prince of Wales launched an appeal to raise money to establish more

of these schools in the empire.

"The blunt reality", laid bare in a 1944 government report, was that the schools "were designed to train unwanted boys and girls from

England to become labourers and

servants on the country's farms", observes the book. Furthermore, in the brave new post-war world of the Fifties and Sixties, the farm

schools were increasingly viewed as an anachronism.

In 1956 a damning fact-finding mission criticised the "institutional nature" of the schools, "the harsh separation of brothers and sisters"

and the children's "continuing isolation". Time was running out for child migration and the last party of child migrants - nine

Barnardo's children - arrived by air in Australia in 1967.

Forty years on, what are we to conclude? Some child migrants undoubtedly made good. For instance, one child sent out by the Waifs

And Strays Society became "a stalwart Canadian, hardworking and law-abiding" who joined "HM forces". Furthermore, most

children sent to the colonies did not return to England, although whether they had the means to do so is debatable.

However many, perhaps most, youngsters struggled to adapt to life in an alien land, felt isolated and lonely, and always carried the

stigma of being a "Home child". In short, for all the good intentions of many of those involved, child migration was an ultimately

misguided attempt to solve a Victorian-era problem - and few would mourn its passing.

|